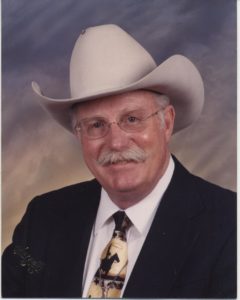

Donald D. Vaniman, License #4125, has been a licensed Real Estate Broker in the State of Montana since June 28, 1979. His office is located at 5020 Westlake Road, Bozeman, Montana 59718.

Don graduated in Animal Science from Montana State University in Bozeman (1963), and has experience as a ranch hand & cattle owner. Prior to Real Estate, he was the Executive Secretary of a Beef Improvement Association and a National Cattle Breed Association Secretary.

Don specializes in listing & selling Montana Farms, Montana Ranch Land, and Montana Recreational properties, and is a one-person office. If he does not have listed what you are looking for, he will be happy to work with you to find that special property you desire. Montana Law specifies that Don can work for you as a Seller’s Agent or a Buyer’s Broker, or (with the consent of both Buyer & Seller) he can act as a Dual Agent.

Don is a member of the National Association of Realtors, the Montana Association of Realtors and the Gallatin (County) Association of Realtors. He is the longtime President of the Southwest Montana Farm & Ranch Brokers, which meets monthly.

Many of Don’s sales have involved IRC 1031 Tax Deferred Exchanges, Charitable Remainder Trusts, Options, Cash and Contracts. He promotes good environmental practices, such as rangeland & cattle improvement and stream restoration. He is also an advocate of Conservation Easements, to protect the scenic beauty, wildlife and agricultural values of Montana’s Big Sky country!

Note: Only Exclusive Listings are advertised on this web site and the site is updated weekly.

Agent for the Land

A broker of ranches and farms for 21 years, Don Vaniman knows agriculture’s past and foresees the challenges of its future

By Nick Ehli / Editor of Fencelines · photos by Doug Loneman / Bozeman Daily Chronicle Published February 2000

Don Vaniman reluctantly admits that he wasn’t born in Montana.

It takes some prodding and he is clearly uncomfortable that perhaps in the minds of some, his nearly 45 years in Montana – most of it working in the ag business – won’t qualify him as a native. What’s worse, he says, is that he was born in California.

“I didn’t have a choice,” he says. He would rather talk about when he first came to Montana as a teenager to work one summer on his great uncle’s spread in Nashua, not far from the Missouri River in the northeast corner of the state. It was then, that Don Vaniman realized where he would live and where he would call home.

“I looked around, and I remember thinking, ‘Man, this is God’s country.’” Now, years later, he still feels blessed to be a Montanan. Despite the seemingly stoic and rough exterior – a thick, handle-bar moustache, gruff voice and the “real men don’t wear polyester” bumper sticker that hangs in his office in downtown Bozeman – he speaks lovingly about the state and, even more so, about the people who ranch and farm here.

“Ranchers are the salt of the Earth,” he said recently. “Some of the finest people you’ll ever meet.”

It’s likely that that affection – coupled with a deep background in agriculture – has made him one of the region’s most sought-after and respected brokers of farm and ranch property. His 21 years in the business also provides him with a unique insight into the past and the future of the state and its agriculture.

After all, he can still remember a time when ranch buyers actually were interested in how many cows could be run on a place.

“Trees, creeks and national forest are the first words we hear from most buyers nowadays,” Vaniman said. “Homesites, that’s what they are buying. It doesn’t matter how many cows you can put on it.”

As with most change, there is good and bad. Vaniman sees some of both. He also sees challenges that Montana will have to meet if there is any hope of retaining the qualities that lured him here in the first place.

“We’re chopping up our open spaces,” he said. “I mean, at some point, we have to ask ourselves: What will this all be like in 30 years?”

Don Vaniman didn’t always buy and sell ranches.

At first, he was drawn to the work on his uncle’s place in Montana, but by the time he was 14 years old in 1955, he was out on his own, contracting hay in the Bitterroot Valley. He had a crew of five or six other young men working for him.

“I would leave home every summer to come to Montana to work,” he said. “Charlie Russell did it when he was 12, so why not?”

Each summer, the U.S. Forest Service would come looking for firefighters, and his crew got scarce. He eventually joined them.

“They told us as soon as we were done haying to come fight fires,” he said. “We got drafted.”

As Vaniman, 59, tells the story, his yellow lab, Carlie, brings a worn tennis ball for him to throw. The owner gladly tosses the ball out into the reception area of his office, and Carly gladly returns it. You can tell this scenario is played out often. Vaniman calls the lab his “official greeter” and jokes that he has probably the only real estate office in town with its own, wandering dog.

His office, at 214 South Willson Ave., is an 1892 Victorian that he and his wife, Cecilia, have restored during the last several years. With an exterior highlighted with purple and pink trim, it’s an easy building to find. Vaniman affectionately calls it “their painted lady.”

With the forest service, Vaniman initially carried a chain saw. In subsequent summers, he was tabbed as a smoke chaser. That meant that a helicopter would drop him off, alone, in the forest to track down and extinguish small, lightening-caused fires.

“They always said, ‘We’ll come back and get you in two days.’ Well, they never came back,” Vaniman said. “I walked out of a lot of forests.”

It was tough work, but he was use to making a few cents for every bale of hay he could stack. The forest service paid $6.50 an hour, and he wanted to go to college. He eventually enrolled in Bozeman at what was then Montana State College. He was awarded his degree in agriculture in 1963.

Within 24 hours after his last class, Vaniman reported to the recruiting center in Butte. He’d been drafted into the army. He served three and a half years at various bases throughout the United States. Three times he was told he was headed for Vietnam. Three times, the order was rescinded as he was about to ship off.

“I guess God had a higher calling for me,” Vaniman said. “I think about that quite often. I lost a lot of friends there.”

“I guess God had a higher calling for me,” Vaniman said. “I think about that quite often. I lost a lot of friends there.”

He keeps that in mind when he does things like joining the foundation that raises money for the Manhattan Christian School, where his only child, Shaun, is a senior. He sees a great need for the Christian school.

“When you take God out, you have no moral values,” he said. “If everybody followed the Ten Commandments, think what a world this would be.”

After the service, Vaniman returned to the Bitterroot Valley and worked for a cattle ranch. After about a year there, he took a job as the head of the Montana Beef Performance Association and put his schooling to use. While many ag schools around the country were teaching students what to look for in the show ring, professors in Bozeman taught Vaniman and others about genes and which characteristics a bull would or wouldn’t pass on. How a bull looks will tell you one thing; how he performs is what matters.

“Once the steak hits the plate, you can’t tell the color of the hide,” Vaniman said.

For the next four years, Vaniman traveled the state, weighing and grading cattle and convincing ranchers that there was a better way to do business. The association’s membership went from 150 to 1,200 in those few years. He eventually left for a job starting the Simmental breed of cattle in the United States.

“I was single and was willing to take the $350 a month they could afford to pay me,” he said.

By the time he left that job in 1978, Simmental was one of the premier breeds in the country, and Vaniman had formed Simmental Associations in 40 states, as well as a world foundation. He had also compiled a listing of every Simmental bull in the country, the first national sire summary of any breed in the United States. Vaniman views that as a milestone in his agriculture career, and such listings are now standard in the industry.

While Vaniman had been successful, he wanted to run his own place. By that time, he’d married Cecilia. They met in a gondola at Big Sky Resort, and this year will mark their 25th anniversary.

Vaniman’s plan was to get into the broker business, sell a few ranches, make a few bucks and then go out on his own. ”I was naive,” he said. “It doesn’t work out that way.”

He has been buying and selling ranches and farms ever since and plans to continue “probably until the day I die.”

When Vaniman started, the cattle ranch business generally went in 10-year cycles, paralleling the ups and downs of cattle prices. It wasn’t too tough of a market to figure. That all changed, he said, when Ted Turner bought his ranch in Montana and owning a spread became fashionable amongst the rich and the famous. Since then, it’s difficult to gauge what somebody will pay for a ranch in Montana.

“Fishermen will pay more than anybody,” he said. “The elk hunters are next. You can almost price your ranch by how many elk you have on it.”

He figure’s it’s only a matter of time before somebody calls and asks about “gophers per acre.”

Those buyers aren’t so much interested in turning a profit. They’ve made their money in a computer company or in the stock market, and “they want to put it in something solid, like a ranch,” he said. Many come for only a few months in the summer.

Years back, the bigger ranches sold at less per an acre than a smaller place would. That’s all changed, Vaniman said.

“The bigger the place, the more money per each acre,” he said. “They are buying privacy, and most of them pay cash.”

Still, he takes pride that during the last several years, more than half of the ranches and farms that he has sold have been bought by Montanans. Vaniman typically has about 20 ranches or farms for sale, from Big Timber to Dillon, ranging from 340 acres to 3,000 and from $650,000 to nearly $4 million.

With such big ticket items, Vaniman could easily hire a professional photographer to go out and take pictures of the property he has for sale. Instead, he takes the photos himself and has a keen eye for capturing the serenity of the land.

He has rubbed shoulders with a few famous customers. He doesn’t drop names, although he does like to tell a story about a bodyguard who came along to protect a prospective ranch buyer. Vaniman showed the bodyguard how to open gates. Fourteen gates along the way. Fourteen times, the bodyguard closed himself in on the wrong side of the fence, and then jumped over.

For the movies “A River Runs Through It,” and “A Horse Whisperer,” Vaniman was consulted about possible filming locations. “They would want a long dirt road leading to a ranch, things like that,” he said.

Rich folks coming to Montana and buying ranches isn’t all bad, he said. Those buyers aren’t interested in subdivisions. They help the economy by building fancy houses and fixing old fences.

“You tell them about weeds, and they spray for weeds.” Vaniman said. “I see most of them as good stewards of the land.”

The prices those people are willing to pay for a ranch or farm, though is certainly changing the makeup of the region. Long-time ranch families will sell their place in Southwest Montana and then move to Eastern Montana or another state. There, they can afford to buy a ranch several times bigger than the one they just sold.

“They are buying with 50-cent dollars,” he said.

What’s worse, he believes, are the ranches and farms that are being bought and then subdivided for homes.

“This whole valley use to be agriculture, and we’re carving it up with houses,” he said. “And the bigger the city gets, the less you know your neighbor. Rural folks know their neighbors, and they’re more likely to help out when they’re needed.”

“Farmers and ranchers raise the moral fiber. I think most believe in God. You have to when you’re hit by a drought one year and a flood the next.”

Still, he doesn’t see changes until the government gives ranchers and farmers more of an incentive to stay on their land and to stay in agriculture. He realizes, though, that that may be a tough sale. He points out that there are more people on welfare in this country than people who work in agriculture.

“What I know is that ag land needs to be protected,” he said, “or it will go away.”